Thought Leadership Studio Podcast Episodes:

Interview with Dr. Brian Sullivan of ADOH Scientific

Episode 53 - Emotii and Dr. Brian Sullivan's Journey of Insight and Innovation. Recognizing opportunities for innovation and bringing them to life, humanizing data gathering and making the subjective objective.

#entrepreneurship, #innovation, #insight, #inspiration, #interviews, #marketresearch, #paradigmshifts, #thoughtleadershipexamples

Or Click here to listen or subscribe on appWhat this episode will do for you

:- Gain Insight into Seizing Innovation Opportunities: Gain profound insights into Dr. Sullivan's journey, where he spotted an opportunity for groundbreaking innovation. Recognizing innovation potential and effectively communicating its benefits can drive success in any marketplace.

- Emotii's Paradigm Shift: Discover Emotii, a revolutionary platform designed to uncover affective determinants of health, ranging from stress to anxiety and depression. We also discuss its possibilities in providing feedback for positive states like focus and confidence. Emotii could also redefine the landscape of subjective information gathering in general.

- Self-Assessment Superpower: Uncover the transformative potential of Emotii's self-assessment feature. Understand how encouraging individuals to evaluate their emotional states can lead to improved self-regulation. Explore how heightened self-awareness can be a catalyst for driving positive change.

- The Symphony of Thought and Feeling: Embrace a paradigm shift as we explore the profound connection between emotions and cognition. Dr. Sullivan illuminates the concept that our minds operate as orchestras, where thoughts and feelings harmonize to drive actions, decisions, and effective communication strategies.

Dr. Brian Sullivan

Meet Dr. Brian Sullivan: Innovating Healthcare with Emotii.

Dr. Brian Sullivan, a seasoned clinical psychologist with over 25 years of experience, is at the forefront of healthcare innovation. Holding a PsyD in Clinical Psychology and a Master's Degree from Florida Institute of Technology, along with a Bachelor's in Psychology from Clemson University, his educational background is as impressive as his career.

Dr. Sullivan's recent notable achievement is Emotii, a platform developed by ADOH Scientific. Emotii enables putting numbers on the reporting of subjective states, with a current focus on scalable distribution for population health research. We also discuss its potential in other areas on the podcast.

Aside from his pioneering work with Emotii, Dr. Sullivan owns Lifeworks, LLC in Mount Pleasant, SC, and is an adjunct professor of psychology at the College of Charleston.

In this episode, where we dive into the transformative potential of Emotii and the process of taking a vision effectively to a market. Join us for an insightful conversation with a healthcare visionary.

Some of Dr. Sullivan's coordinates:

Curated Transcript of Interview with Brian Sullivan, PsyD

The following partial transcript is lightly edited for clarity - the full interview is on audio. Click here to listen.

Chris McNeil: I'm your host Chris McNeil, with Thought Leadership Studio, and I'm sitting here with Dr. Brian Sullivan, who's a licensed clinical psychologist, but he's also the chief science officer and the originator of the technology behind Emoti, a new app being unleashed to the world by ADOH scientific. Welcome, Dr. Sullivan. Great to have you here.

Brian Sullivan, PsyD: Thanks Chris.

Brian Sullivan, PsyD: Thanks Chris.

Chris McNeil: So what inspired the innovation? What happened or was there a pivotal moment where you realized the need for something like Emotii to do what it is that we'll end up describing to the audience in a minute, of course.

Brian Sullivan, PsyD: Yes, absolutely. I had been practicing a number of years as an applied psychologist and I attended a conference, the American Psychological Association's Practice Organization dedicated to practitioners as opposed to academics and researchers. And I sat in on a panel discussion where several psychologists were talking about what became eventually to be known as measurement-based care.

And that is simply quantification of critical variables that help to inform service delivery, that help to inform improvement of service, that help to render data that can be used for predictive purposes, like trying to predict which patients are most likely to improve, which patients might terminate unilaterally early without continuation of service, those types of things.

And this was all in psychology. This was all around the difficulty of taking what is a very intimate personal and often esoteric practice psychotherapy and translating it into useful data points. And so these researchers were developing instruments to capture certain types of experiences that people report when they seek services and along the course of care, including the quality of the therapeutic alliance, their sense of comfort in the office, what types of difficulties they have been experiencing, what sorts of goals they're trying to achieve, trying to take those things and turn them into quantifiable data that could be used to monitor progress and to help the clinicians to improve their service delivery and the quality of cares along with the patient experience.

And I got very excited. This was many, many years ago and this was new to me. I had never been in the habit. I of course used diagnostic instruments that required folks to fill out questionnaires to report whether they had been experiencing difficulties with their mood, with their behaviors around eating substance use, et cetera, but I had not been using anything that would help me to actually capture and quantify and monitor their progress.

So I relied on them to tell me whether or not they were improving. I had my own clinical impressions as well, but none of that was being translated into data. These researchers were at the forefront of trying to develop that technology to capture and measure these things.

Making the Subjective Objective

Chris McNeil: (Making the) subjective objective, basically? How to make it something we can track - and does that have to do with "How do we know that what we're doing is working for a patient?"

Brian Sullivan, PsyD: Exactly. And to allow us to compare our own performance across time, to compare our own performance across patients, and to compare our own performance to that of other clinicians treating people with similar concerns, treating people who were similar or different in meaningful ways than those that we were seeing that sort of thing. Exactly. Yes.

Chris McNeil: Interesting. Well, Wasn't it Einstein that said not everything that counts can be counted and not everything that can be counted counts, but we have to take these things into account and I know sometimes in the practice of using systems thinking for organizational development, you have to bring in subjective variables like morale that the scientist in the group might say, "Well, you can't objectively measure that", but it doesn't mean it's not really important.

And what it looks like to me from here is that you're developing a tool to better translate subjective experience into something that can be useful for seeing change in time and for making diagnoses and for perhaps prescribing treatment based on that. Is that correct?

Brian Sullivan, PsyD: Yes, and measuring outcomes, helping to ensure that we are achieving the outcomes that we intend to and using best practices to get there.

Chris McNeil: Interesting. Has there been any use of anything that can correlate things that are objectively measurable without having to depend on subjective reporting - like biofeedback - with this yet?

Brian Sullivan, PsyD: We have not done any of that work ourselves, although it must be said that the type of data that we are capturing and measuring, quantifying and turning into useful insights absolutely is set up to be combined with other data types such as that, which would come from wearable devices through biofeedback sessions, through objective measurement of weight or of food intake or of minutes and heart rate variability, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera.

Brian Sullivan, PsyD: We have not done any of that work ourselves, although it must be said that the type of data that we are capturing and measuring, quantifying and turning into useful insights absolutely is set up to be combined with other data types such as that, which would come from wearable devices through biofeedback sessions, through objective measurement of weight or of food intake or of minutes and heart rate variability, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera.

Chris McNeil: Yeah, I was just thinking as I was taking my own practice experience of it a few minutes ago, and it's interesting, it's really easy - and it's a lot easier than like you were mentioning earlier when we were speaking before we recorded, than having to just rate yourself on a one to 10 scale - instead just move this slider over to where you think you are.

But it makes me wonder what some of these correlate with blood pressure, heart rate, breathing pattern, things that could be objectively measured and brought into the loop somehow maybe as a calibration exercise. I'm just thinking out loud. It's a very fascinating product to me.

Brian Sullivan, PsyD: Thank you. It is fascinating because when I began adopting the well-validated instruments to capture the patient's experiences across time, I learned something and this was part of the pivotal moment. People generally don't enjoy filling out questionnaires.

Innovation Opportunity - Removing Friction

Chris McNeil: Seriously?

Brian Sullivan, PsyD: (laughs)

Chris McNeil: I'm just joking ...

Brian Sullivan, PsyD: I actually observed patients using these gold standard instruments that had been designed and validated by other researchers and were typically set up with what we call Likert scale reporting methodology. How depressed have you been feeling? Zero to five, zero, not at all. Five extremely. And I watched people skipping through these multi item questionnaires, some of them having 10 items, some of them having 45 items, and they would circle zeros on everything. They came in for a psychotherapy appointment, they'd circle zeros on everything.

Brian Sullivan, PsyD: I actually observed patients using these gold standard instruments that had been designed and validated by other researchers and were typically set up with what we call Likert scale reporting methodology. How depressed have you been feeling? Zero to five, zero, not at all. Five extremely. And I watched people skipping through these multi item questionnaires, some of them having 10 items, some of them having 45 items, and they would circle zeros on everything. They came in for a psychotherapy appointment, they'd circle zeros on everything.

Well, I don't score zeros on everything on my best day, and so I would say That's interesting. It looks like you're doing fabulously. No, I'm not. My life is terrible. But you circled zeros on everything. Yeah, because I hate your stupid survey. Oh yeah. Do I have to fill this out? Well, yes. It's part of our clinical procedures.

It's part of our quality assurance methods. Yeah. Well, I don't enjoy doing this. Okay. I would watch people circle all fives on everything and making themselves look like absolute train wrecks, but that was not actually the case. Long story short, I noticed that I was not getting valid data from a lot of the people who were filling these things out.

Other folks would take 20 minutes to fill out what should have been a five minute questionnaire because they would circle a three and then they would cross that out and circle a four and cross that out and go back and boldface the number three and then start writing in the margins trying to explain why. Well, it wasn't really a three, it wasn't really a four. Or they would flip the page over and start writing a narrative. And I literally had one patient at one time look up from the clipboard and he said, doc, I don't feel in five point gradations.

I said, yeah, I understand, but this is the state of the art and we're trying to do a good job here. He said, I get it. I said, just do your best. And he did. We got through that. But the biased data, the fact that people were not in many cases filling it out faithfully, they weren't properly reading the items.

They may have been confusing or too lengthy or simply the questionnaire was too lengthy or the whole process was tedious and it was actually perceived as a barrier to what they really wanted, which was to be able to talk, to be able to actually relate with me to spend their time doing the work rather than spending their time filling out questionnaires. And I thought there just has to be a better way. There's a small number of common denominator issues that people typically report irrespective of the specific details as to why they feel the way they do.

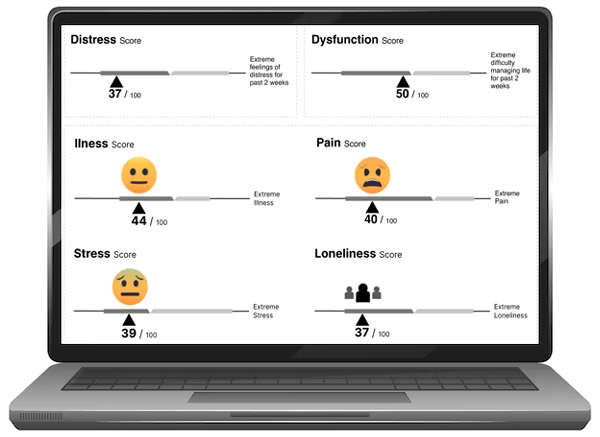

It was the feelings that mattered most to them. Those were the things they most wanted to alter, not because the behaviors weren't important, but the behaviors were outflows of the feelings. Feelings are primary motivators and drivers of our decisions and our behaviors. And that small cluster, I thought, wouldn't it be nice if I could just hand them a tablet device with some graphical depictions of feelings?

Here's a depiction of depression, here's one of anxiety, here's one of pain, here's one of fatigue. And allow them to just dial that image up and down in terms of the intensity of the expression and let them show me how they've been feeling rather than trying to quantify for themselves by circling a three. Wouldn't it be nice if they had something like a mirror and they could dial it up and go, no, I don't feel that bad.

And they dial it down and go, no, I feel worse than that. And then reach that Goldilocks moment of right there, that's just about how I've been feeling lately, and then stop, move on to the next one, depression, scale it up and down right about there. Okay, move on. Anxiety, scale it up and down right about there.

And they dial it down and go, no, I feel worse than that. And then reach that Goldilocks moment of right there, that's just about how I've been feeling lately, and then stop, move on to the next one, depression, scale it up and down right about there. Okay, move on. Anxiety, scale it up and down right about there.

And the quantification would happen in the background. They would not see numbers. They would use what we call a digital affect mirror to show us how they feel and that would be useful data in and of itself.

And then in the background at the database, there would be a quantification of what they dialed in and our e motis render scaled values on a zero to 100 scale each one of them, and then we translate that into a composite score for everything that they have entered.

We also use an in combinatorial analytics to predict against various outcomes or progressions. We combine it with social determinants of health data. We can combine it with all manner of other types of data like from wearables, from clinical data, from their charts, et cetera, and produce a whole new data set that represents these core critical normal feelings that when they become normal because of the intensity, because of the duration, because of the impact on their decision-making and their behaviors, they become of true clinical relevance.

Chris McNeil: I see an interesting thread here, and I'm going to dive in if you don't mind, as the listener advocate, thinking from the position of "what does this mean to me? I'm a leader, I'm an entrepreneur, I'm an innovator myself. What can I learn from this?" And one of the interesting threads I'm seeing so far is something that's fascinating to me anyways is the nature of self-assessment itself.

From Self-Monitoring to Self-Regulation?

And I'm somewhat familiar with the concept of self-awareness and self-regulation, and this is in part from when I was an athlete. I actually worked with a sports psychologist who'd worked with a couple of US Olympic teams and we used a visualization exercise of imagining a meter corresponding to activation level before I did a heavy set of squats, for instance, I would dial it up to a 10 and I'd feel my energy increasing and my focus narrowing, my muscles tensing and my energy increasing ... and then I'd turn it back down.

Which leads me to question about the effect of by monitoring yourself this way, does that not lead to regulating these things more consciously? Because if you got to rate yourself on the scale, you got to at least think about what it'd be like to be at the best end of the scale and create that model in your mind of what I'd be like if I wasn't depressed or if I felt great and things like that.

Brian Sullivan, PsyD: Absolutely. One of the wonderful side effects of this method, this intensely visual method, which by the way holds worldwide promise because of being more language agnostic and more culturally fair than traditional methods. This process of tuning in with yourself with the aid of this technology to actually inquire of yourself. Yeah, exactly.

How anxious have I been? Exactly how lonely have I been? What is my pain rating when I look at this thing? Oh, okay, I know I don't feel quite that much pain, but I feel more pain than that. Let me fine tune right there that's about how much pain I've been feeling. And to think back, oh, well, it is worse than it was the last time I filled this out. And we have designed this for repeated administrations because it's really important to capture the variability of these things across time or the lack thereof because these are feelings that should vary across time.

And so when we capture data that suggests the variability is actually pretty minimal, while the intensity is pretty high, that's bad. No one wants to feel like that in a durable way. No one wants to go on and on. These are all feelings that we are naturally motivated to try to reduce, to try to bring down the intensity of stress, anxiety, loneliness, irritability, depression, pain, fatigue and physical illness or malaise. None of those feel good.

And we are naturally motivated to try to bring those down. And the big problem is many of the ways that we try to reduce our awareness of those feelings, the intensity of those feelings is actually bad for us. Substance abuse is one of the easiest examples. One of the easiest ways for us to blot out a negative feeling is to ingest a chemical that changes how our mind operates and our perceptions are registered. Okay, so that works for the moment, but there's often such a high price that's being paid in terms of our ability to relate to others, our ability to get our work done and the long-term impact on our health.

Chris McNeil: Well, something I noticed about it, and correct me if I'm wrong because I don't have it in front of me now, and I just had a brief introduction, is that it focuses a lot on states that we don't want, but could it not also be used for states that we do want like confidence, feeling highly energized, feeling in control, being able to focus, which is a big issue in today's society because the internet and social media has trained a generation to be very distractible.

Chris McNeil: Well, something I noticed about it, and correct me if I'm wrong because I don't have it in front of me now, and I just had a brief introduction, is that it focuses a lot on states that we don't want, but could it not also be used for states that we do want like confidence, feeling highly energized, feeling in control, being able to focus, which is a big issue in today's society because the internet and social media has trained a generation to be very distractible.

Brian Sullivan, PsyD: Absolutely. You just touched on something critically important, those eight key affects that I've just described. First, let me say when I use the term affect, I am referring to the collection of emotions, moods, and other subjective experiences that have an emotional nature. Pain is a subjective experience. We cannot measure that objectively. There's no dipstick that we can stick in someone's ear to measure their pain level. And only a moment's reflection will highlight for you that pain feels bad, that doesn't feel good.

I am motivated to reduce or avoid pain when I can. I am motivated to reduce or eliminate depression if it's possible. It's normal to feel sad, even depressed at times as in grief. And those things can be intensely distracting. So we call all of these drags. These are things that all exert a drag against a number of things that we need to be able to do in life, like be productive at work, relate well with others.

Irritability is a key example that gets in the way of being able to relate well with others because we wind up pushing people away when we're irritable. And usually that's the very last thing that we want. We want to have close well connected relationships. Our irritability gets in the way of that. Our depression can get in the way of that. Our anxiety can get in the way of that our pain can even get in the way of that. It impairs our ability to follow treatment plans. These things get in the way of what we call treatment adherence. I'm not motivated to get up and exercise to recover from my surgery because it hurts, so I'd rather just sit and minimize the pain.

But actually that's the wrong solution. You need to exercise that joint in order to help it in its recovery. You need to do your physical therapy exercises that have been prescribed. These things often motivate us to do things that actually harm us in the short and in the long-term. They all have physiological artifacts that contribute to maladaptive coping efforts. They may be symptoms of actual disorders and diseases. They may appear to be mental health artifacts when really they are correlates of underlying fundamental physical disability, physical maladies, physical disease.

Chris McNeil: It seems that by having the increased self-awareness, it opens the opportunity for questions like can you imagine how your life would be different if you rated very well on these measures you're not now? Yes, I imagine that would also assist people like yourself who might be counseling people who are prone to addictive behaviors to have a little more self-awareness about not doing things that damage the whole system while giving temporary relief.

Brian Sullivan, PsyD: 100%. And one of the joys in my actual day-to-day practice is being able to print out a temporal graph of their progress across time and be able to sit down with them and say, Hey, check this out. You started at this composite of all of this affective load, these negative experiences way up here. And look, we started working together and you started to get better pretty quickly, and there's this nice dose response curve.

And look how you've been doing lately. You've been holding at a relatively low overall level and these two aspects that were bothering you the most when you came in. Look how much we've helped you to bring those down and think about the skills that you have developed across time that have rendered those results. Now, interesting. It might be time to fire me. I always tell my patients, my job is to get fired.

My job is to work myself out of a job. My job is to help you get to the point where you smile and fire me and shake hands with me and say, I'm really glad I've done this and I'm done. And then two years later, you struggle to remember my name, but you still remember everything that we did to help you in that progress and in that recovery, so that hopefully you never need to darken my door again. Problem solved. Yes, problem solved.

You mentioned the of using the Emotii method to capture things on the lift side as opposed to the drag side, things like self-esteem, self-efficacy, motivation levels. Absolutely, that potential is there and we intend to tackle those things further down the road. In our roadmap, we decided to start with these more negative experiences because the scientific literature is much more complete and much more sophisticated and thorough as to the deleterious health effects of this collection than it is on the positive side.

Chris McNeil: Well, that's the paradigm of modern medicine though, isn't it? Modern medicine is very much focused on break it, fix it when it's broken, so focus on what's broken. But then you've got the generative change aspect of how high is high, how happy can you be? How productive, how good can you feel? How large a contribution can you make to others as a result of this? And another thread, I'm trying to capture some threads here that are really relevant to things like strategic thought leadership.

Another one, feelings or drivers that's very important to anybody in any kind of influence, whether they're looking to engineer positive social change with a philosophy about how we treat each other and impact regulation or impact the laws as a result of that, or whether it's bringing innovation to market and changing. People make decisions based on feelings in my experience. And when you look at it from a sales and persuasion and marketing perspective, emotions drive decisions, and then the logic just kind of comes into support. Those emotions build a logical argument so we can do what we feel like doing.

Another one, feelings or drivers that's very important to anybody in any kind of influence, whether they're looking to engineer positive social change with a philosophy about how we treat each other and impact regulation or impact the laws as a result of that, or whether it's bringing innovation to market and changing. People make decisions based on feelings in my experience. And when you look at it from a sales and persuasion and marketing perspective, emotions drive decisions, and then the logic just kind of comes into support. Those emotions build a logical argument so we can do what we feel like doing.

The Mind as an Orchestra

Brian Sullivan, PsyD: One of the key developments in neuroscience and affective science has been the realization that the longstanding bifurcation of emotions and cognition or emotions and rationality, if you will, is absolutely false. They are not separable. They are not separable. There are some great researchers like Antonio DeMaio and others who have done a great deal of work of demonstrating that thought. And feelings are more like bunt cake, where it's all mixed together rather than the traditional view of one being a layer with another layer on top or one being beneficial and the other being deleterious. Those old models are wrong. Our minds work in concert. It is an orchestra.

***************************************

The transcript is lightly edited for clarity and is a partial transcript- the full interview is on audio. Click here to listen.

***************************************

Free Stuff and Offers Mentioned in Podcast

***************************************

***************************************